I had a series of nice New York moments this weekend, in addition to the fact that it is snowing right now and Brooklyn always looks beautiful in the snow.

I was on the subway last night and an older gentleman got on with a friend and his 12 string guitar. He looked like "Old Bluesman" straight out of central casting, but when he began playing guitar, it was anything but the standard blues (the music of complaint). It was beautiful, soulful, soft and hypnotic. He seemed to be playing for his friend rather than money. When he was finished, the two of them talked rather than getting up and passing the hat.

At the next stop, a group of four Mexicans got on the car with their instruments: guitar, accordian, stand up double bass, and hat. Yes, one member of the group was only there to pass the hat for donations. I'm assuming they were Mexicans because their first song was that "Aye-yi-yi-yi-I am a Frito Bandito" song, but they could have been from Honduras or El Salvador. I was half-expecting a battle of the bands between them and the Old Bluesman, but he just listened to them play while continuing to talk with his friend. Someone one the subway was eating an orange and its scent perfumed the entire car.

The best occured this afternoon while taking the subway to Manhattan. I was reading a book when suddenly I heard someone singing the "Ave Maria." I looked around the car expecting to see the standard robust opera singer (again, right out of central casting) and was surprised to see the incredible sound coming out of a rather slight, unassuming young lady. I guess I should count myself lucky that it wasn't a fat lady, cause that would mean that it was over. Regardless, the girl was able to sing the "Ave Maria" in a way that resonated throughout the subway car, her beautiful voice completely saturating and subduing everything else going on the the car.

It was absolutely beautiful, one of those unexpected moments in life that you treasure.

I gave her a dollar.

Sunday, February 25, 2007

Friday, February 16, 2007

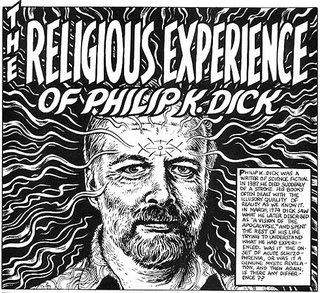

03.42 What If Our World Is Their Heaven?

What If Our World Is Their Heaven? The Final Conversations of Philip K. Dick

Edited by Gwen Lee and Doris Elaine Sauter

Philip K. Dick is my favorite science fiction writer. Philip K. Dick is a lot of people’s favorite science fiction writer. I don’t know if it’s because he flatters the reader’s sense that no matter how lost they feel their lives serve a greater purpose or because his great theme was the way in which an individual’s sense of reality may not correspond with everyone else’s. Maybe it’s because he’s less concerned with those who invent shiny rocketships than with those who have to clean them. Regardless, he’s one of the few science fiction writers who is taken seriously by those who don’t read science fiction and with good reason.

What If Our World Is Their Heaven is a collection of interviews Dick conducted a few months before his death. Knowing that he died a few months later adds a special poignancy to the proceedings, whether he is enthusiastically discussing the first big budget film based on his writings (Blade Runner) or describing a fictional character who willingly gives up his life in exchange for spiritual revelation. Beyond that, the book is an interesting example of a mind at work, or, as Robyn Hitchcock once put it “the odd act of a mind trying to explain itself.” Dick describes a novel he would never live to write, working it out while talking about it -- it’s fascinating to witness a writer at work. The novel concerns an alien from a world in which they communicate through color / light frequencies rather than sound, so that when one of them arrives on Earth and confronts sound for the first time, he has no concept of it and is convinced that he is having a religious experience. (Hence, the title of this book). This alien mind invades that of a hack composer who experiences truly beautiful music for the first time, and is willing to give up his life for more.

Dick was adept at talking about epistemology and philosophy, about how we perceive light and sound or the history of ancient religions, all without losing his sense of humor or wonder. Hearing his voice directly, without the filter of his fiction, is a treat for his fans or anyone interested in the “oh, wow!” aspects of science.

Sunday, February 11, 2007

Since You Asked...

In the comments section to the previous entry, Iva (aka my mother) asked:

"Can anyone tell me why we started this war (with any kind of logic at all?)"

Okay - my take on why:

They (not "we") decided that the U.S. needed a Western-friendly region in the Middle East. (When we say "Western-friendly" what we're mainly talking about is "friendly to Western business interests" but our political system is so entwined with our economic system that most in government can not picture one without the other). Basically, they wanted a US-friendly puppet government, similar to what the Soviets created in Eastern Europe during the cold war. In addition to access to Iraq's resources, the US would be able to establish the military bases necessary for gaining more control of the region.

Our other ally in the region, Israel, has never been stable enough for the US to use as a base of operations without creating a full-blown occupation. And Israel's problems are going to get worse, not better. I read an article a while ago that mentioned that Israel's population is declining and a number of younger Jews don't want to live in war-zone, whereas the Palesinian population has been increasing. Within a generation or so, the Israelites will be surrounded by even more people unsympathetic to their cause and in need of what few resources they have. The name "Custer" comes to mind.

So the Middle East was the Gordian Knot and invading Iraq became the answer to all of the US' problems. Want a Western-friendly region in the Middle East but want to avoid a conflict with Islamic clerics? Invade Iraq - a country with a secular leader unpopular with much of the Arab world. Need access to oil to put off the coming energy crisis as long as possible? Invade Iraq - second largest oil reserves in the world. Need a home for military bases from which we can, when the time comes, start moving into other countries? Invade Iraq. Need a country we know we can beat since we did it 15 years ago? Invade Iraq.

I'm sure there were other questions I don't even know about which "Invade Iraq" was the answer. Hussein was a US ally in the 80's - I'm sure he had some dirty laundry that the Bush administration preferred be burnt. It wouldn't surprise me if Saudi Arabia mentioned they'd like a US-friendly Iraq as a buffer between them and the rest of the Arab world.

This sort of theorizing ("We want to control this, how do we do it? If we do this, how will another country react?") is what conservative thinktanks do. It's what they're for: endless theoretical arguments are created, predictions made, schemes hatched. Most of those schemes come to nothing because there's no way to legally put them into practice. But with the carte blanche given to the Bush administration after 9/11, neo-conservatives seized on a rare opportunity and decided to invade another country on manufactured pretenses according to plans drawn up in right-wing thinktanks.

I'm sure the original plan was for a quick war and takeover of Iraq, then, after a year or two, boostered by support from the American public, begin the process again with another country. Syria: maybe. Iran, if feeling particularly ambitious. However, it didn't work. For all their funding and ideas, the conservative think tanks were wrong. No plans for post-invasion Iraq were made because (it sounds incredible) the planners of the war truly believed that the Iraqis would fall in line and create a mini-America once Hussein was gone.

In an interview with Salon.com, Seymour Hersh, author of Chain of Command: The Road From 9/11 to Abu Ghraib, was asked what he thought the real purpose of the war was. Hersh replied:

"...But these guys, do you realize how much better off we would be if they really were cynical, and they really were lying about it, because, yes, behind the invasion would be something real, like support for Israel or oil. But it's not! It's not about oil. It's about utopia. I guess you could call it idealism. But it's idealism that's dead wrong. It's like one of the far-right Christian credos. It's a faith-based policy. Only it wasn't a religious faith. It was the faith that democracy would flourish.

"Q: So you don't think that this is some Machiavellian, cynical, manipulative ...

"I used to pray it was! We'd be in better shape. Is there anything worse than idealism that doesn't conform to reality? You have an unrealistic policy."

So that's my take on why we invaded Iraq: a grand experiment in imposing a "democracy" overseen by the US on an unstable region with a history of inter-tribal conflicts. Neo-conservatives and the Bush administration truly believed that they could transform the Arab world by converting it to a Western-style democracy. Other nations would see how well it worked in Iraq and change their governments and the region would become more stable. It's odd that Bush would be such a fan of democracy, considering how he had to circumvent it in order to become president. But, as I've written before, my cynicism and finding little ironies doesn't help the horror of a situation that has claimed the lives of thousands of innocent people.

"Can anyone tell me why we started this war (with any kind of logic at all?)"

Okay - my take on why:

They (not "we") decided that the U.S. needed a Western-friendly region in the Middle East. (When we say "Western-friendly" what we're mainly talking about is "friendly to Western business interests" but our political system is so entwined with our economic system that most in government can not picture one without the other). Basically, they wanted a US-friendly puppet government, similar to what the Soviets created in Eastern Europe during the cold war. In addition to access to Iraq's resources, the US would be able to establish the military bases necessary for gaining more control of the region.

Our other ally in the region, Israel, has never been stable enough for the US to use as a base of operations without creating a full-blown occupation. And Israel's problems are going to get worse, not better. I read an article a while ago that mentioned that Israel's population is declining and a number of younger Jews don't want to live in war-zone, whereas the Palesinian population has been increasing. Within a generation or so, the Israelites will be surrounded by even more people unsympathetic to their cause and in need of what few resources they have. The name "Custer" comes to mind.

So the Middle East was the Gordian Knot and invading Iraq became the answer to all of the US' problems. Want a Western-friendly region in the Middle East but want to avoid a conflict with Islamic clerics? Invade Iraq - a country with a secular leader unpopular with much of the Arab world. Need access to oil to put off the coming energy crisis as long as possible? Invade Iraq - second largest oil reserves in the world. Need a home for military bases from which we can, when the time comes, start moving into other countries? Invade Iraq. Need a country we know we can beat since we did it 15 years ago? Invade Iraq.

I'm sure there were other questions I don't even know about which "Invade Iraq" was the answer. Hussein was a US ally in the 80's - I'm sure he had some dirty laundry that the Bush administration preferred be burnt. It wouldn't surprise me if Saudi Arabia mentioned they'd like a US-friendly Iraq as a buffer between them and the rest of the Arab world.

This sort of theorizing ("We want to control this, how do we do it? If we do this, how will another country react?") is what conservative thinktanks do. It's what they're for: endless theoretical arguments are created, predictions made, schemes hatched. Most of those schemes come to nothing because there's no way to legally put them into practice. But with the carte blanche given to the Bush administration after 9/11, neo-conservatives seized on a rare opportunity and decided to invade another country on manufactured pretenses according to plans drawn up in right-wing thinktanks.

I'm sure the original plan was for a quick war and takeover of Iraq, then, after a year or two, boostered by support from the American public, begin the process again with another country. Syria: maybe. Iran, if feeling particularly ambitious. However, it didn't work. For all their funding and ideas, the conservative think tanks were wrong. No plans for post-invasion Iraq were made because (it sounds incredible) the planners of the war truly believed that the Iraqis would fall in line and create a mini-America once Hussein was gone.

In an interview with Salon.com, Seymour Hersh, author of Chain of Command: The Road From 9/11 to Abu Ghraib, was asked what he thought the real purpose of the war was. Hersh replied:

"...But these guys, do you realize how much better off we would be if they really were cynical, and they really were lying about it, because, yes, behind the invasion would be something real, like support for Israel or oil. But it's not! It's not about oil. It's about utopia. I guess you could call it idealism. But it's idealism that's dead wrong. It's like one of the far-right Christian credos. It's a faith-based policy. Only it wasn't a religious faith. It was the faith that democracy would flourish.

"Q: So you don't think that this is some Machiavellian, cynical, manipulative ...

"I used to pray it was! We'd be in better shape. Is there anything worse than idealism that doesn't conform to reality? You have an unrealistic policy."

So that's my take on why we invaded Iraq: a grand experiment in imposing a "democracy" overseen by the US on an unstable region with a history of inter-tribal conflicts. Neo-conservatives and the Bush administration truly believed that they could transform the Arab world by converting it to a Western-style democracy. Other nations would see how well it worked in Iraq and change their governments and the region would become more stable. It's odd that Bush would be such a fan of democracy, considering how he had to circumvent it in order to become president. But, as I've written before, my cynicism and finding little ironies doesn't help the horror of a situation that has claimed the lives of thousands of innocent people.

Thursday, February 08, 2007

02:42 Imperial Life In The Emerald City

Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq's Green Zone

by Rajiv Chandrasekaran

It’s like something out of a novel by J. G. Ballard: a gated community filled with all the comforts of the western world located incongruously in the middle of a war-ravaged country. Or perhaps it owes more to Paul Bowles, with its tale of Americans, led predominantly by their own naiveté or arrogance, being completely undone by the Arabic world. But it’s hard to imagine a better depiction of why the U.S. occupation of Iraq is, and was always doomed to be, a colossal failure than Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s record of the year he spent inside Baghdad’s “green zone.”

The “green zone” is the heavily fortified base of the Coalition Provision Authority, located in and around Saddam Hussein’s former palace. Think “green” as in naïve or “green” as in money, and you have a summary of the U.S. occupation. After Baghdad fell, the Coalition Provisional Authority were in charge of stabilizing the rest of the country. But many people were hired for the CPA based not on their qualifications but on their loyalty to the Bush Administration or the Republican party. Even some of those interviewed seemed surprised that they were hired and sent to Iraq.

A pattern repeats throughout the book: someone who knows very little about Iraq is hired to help rebuild part of the country’s damaged infrastructure. They are usually well-meaning and have some good ideas, though often inappropriate or unworkable. Once in Iraq, they discover that they are literally starting from scratch: the widespread looting that began after the war, which the Pentagon was warned about and did little to prevent, has stripped much of the country of its basic infrastructure. (Looting is such a common theme that by the time I was on page 100, I checked to see if it was in the index, curious to see how often it was mentioned. Sadly, no entry for “looting.”) Faced with few resources and an almost impossible task, some sink into cynicism while others try as best they can, but achieve little before they return to the U.S.

There are many times in Imperial Life in which the culture clash is so obvious and funny that you don’t understand why those living through it don’t see it. A recent college grad, who knows nothing about finance, is hired to re-build Iraq’s stock exchange. Opportunists win a contact to guard Iraq’s major airport for millions of dollars even though they have never run a security operation before. A media consultant is hired to create a television news service in the country, but soon runs afoul of the military for not broadcasting enough “positive” news about US efforts.

But perhaps “funny” is the wrong attitude to take here. My bemusement at others’ foolishness is tempered by knowing the chaos that the Bush administration has unleashed on that country. It’s hard to laugh about cross-cultural ignorance when said ignorance has cost tens of thousands of people their lives (and that’s a conservative estimate – pun intended). Recently, after a night out, I had a drunken argument about Iraq with a friend of a friend, who quickly resorted to the “isn’t it good that we got rid of Saddam Hussein -- do you wish he was still in power?” “I don’t see much difference” I replied. “He killed thousands of people, and now we’ve killed thousands more. I’m sure the people who died in the war wished he was still in power. We’ve lost that moral argument.”

“Yeah, but things might get better now…” he answered.

Another green zone.

Wednesday, February 07, 2007

Quote of the Day

From over here, I couldn't tell if you were yelling or just complaining.

- Said to me by a co-worker, 2/7/07 1:28pm

Tuesday, February 06, 2007

01:42 Bottomfeeder

BottomFeeder

B.H.Fingerman

FULL DISCLOSURE: The author, B. H. Fingerman, is a friend of mine, though this doesn’t mean that I’ll automatically like his novel. This past year I read a novel by a woman I went to grad school with, and while I admired the craft with which she wrote her book, I didn’t care for the book itself. It’s very uncomfortable when you don’t like the work of friend or acquaintance. It becomes a void all of your conversations dance around.

But I liked Bottomfeeder. The main character, Phil Merman, is a vampire but is neither self-aggrandizing nor self-pitying. He’s just sort of getting on with it. Goes to his job (at night, of course) at a photo archives and occasionally, when hungry, feeds on a human being. Phil preys on those who will not be missed, society’s outcasts, and one gets the sense that this is as much out of a desire to spare a victim’s loved ones any undue pain as it is an attempt to keep his feeding habits private.

Without being obvious, the book poses a basic existential question: what exactly do you do with your life? The fact that the vampires in the book have eternal life only compounds the problem for them. There are those have enough trouble filling 70+ years. But perpetual existence? Some sink into decadence, some make attempts to help other vampires, and others (like Phil) just live their existence day to day, without too much consideration of where they are going and what it all means.

Bottomfeeder is also a good New York novel, one that actually has scenes in Queens and Brooklyn as well as Manhattan. It captures the “Let’s Make A Deal” feeling in New York that anything could be behind any door. It could be an orgy or it could be a group therapy session. As one who still walks around Chinatown thinking to himself “I just know there’s an opium den around here somewhere” this sense of New York’s chaotic yet stable mix felt true.

The above description doesn't hit at how funny the book is. Phil’s point of view is sardonic and bemused by the actions of both the living and the undead. The voice recalls a tough guy private eye, and this could be both an homage to pulp novels and a comment on how such genres have influenced how we think and talk. There’s a sense of characters wanting to play at what they are not. Whether it’s a vampire orgy that Phil senses is just trying too hard to be “bad,” or an annoying friend who speaks with a British accent even though he’s not British, everyone seems to be trying on a persona, and Phil is there to helpfully mock them.

Sunday, February 04, 2007

New Graffiti Murals From My Neighborhood

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)